The Energy Efficient Building: Passive Heating and Cooling

One way to increase energy efficiency in a home or building is to use passive heating and cooling techniques. These take advantage of such things as the heat from sunlight, shade from trees, air currents within a building and breezes on the outside, and the ability of solid materials (including the ground) to retain heat from direct sunlight or stay cool when shaded. Passive techniques were used throughout history. But as we developed ways to heat rooms, through fireplaces and, later, central heating and cooling, passive techniques were ignored. However, increased concerns about carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from fossil fuel-based heat or electricity have brought a resurgence of interest in methods of heating and cooling that have a minimal impact on the environment and global warming.

Photo courtesy of Dan Chiras This custom-built passive house in Colorado uses many different strategies for heating and cooling without using fossil fuel. |

A passive house uses as little outside energy as possible to heat and cool the building. A fully passive house is not so simple to accomplish. Building from scratch in a well-suited location, with access to or space for an alternative energy source—such as solar panels or a windmill or wind turbine—is a very rare occurrence. Such passive houses are unique. But many passive techniques can be included in more typical-style homes, especially in gentle climates without long periods of extreme heat or cold.

Looking Back: Passive Methods in Nature and throughout History

To increase energy efficiency, many people have looked to ancient passive heating and cooling techniques. The ancient Greeks and Romans and the Pueblo Indians of the United States all knew to position their buildings so that the most commonly used parts faced the equator, where they would get the most sunlight throughout the day. Materials such as stone and adobe-covered hay bales absorbed the heat of the Sun, releasing it during cooler nights.

|

Photo courtesy of Kelly Hart This house faces south to maximize solar heat in the winter. Inside, there are walls and floors with thermal mass to absorb the heat and warm the house. The overhang protects the house from the high-angle summer sun. |

|

|

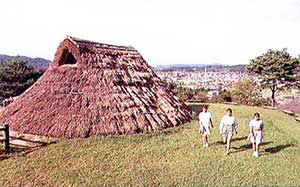

From the Middle to the Final Jomon Period (2500 to 300 BCE) in Japan, people lived in pit houses. These buildings were dug up to 1.5 m (5 ft) into the ground. Tall columns held up the roof. The pit house seen here is a reconstruction located in Kushiro Marsh, Hokkaido. |

The Viking Reserve at the Museum of Foteviken, in Malmo, Sweden, includes a pit house. This type of house usually not include a hearth, and it is believed to have been used during the summer as a crafter’s workshop. |

|

|

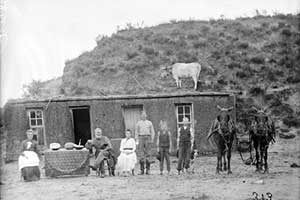

Sod houses, dug out of the prairie, were common dwellings for settlers on the Great Plains of the United States. The family of Sylvester Rawding lived in this sod house in 1886, in Custer County, Nebraska. |

Makam Mahsuri (Mahsuri Mausoleum), a historical site in Langkawi, Malaysia, includes an example of a traditional home. The exterior walls consist of shutters that can be opened and closed as needed. The stilts permit cooler air near the ground to move up into the house, and the high peaked roof includes vents to let warmer air rise up and out. The flow of the air also helps cool the house. |

|

Around the world, in places as diverse as Scandinavia, Africa, Japan, and the plains of the United States, people have dug into the ground for shelter. Earth-sheltered buildings take advantage of the cool ground temperature in the summer and the warmth of it in the winter. Pit houses or dugouts have varied in style, from holes with sloped roofs to buildings dug into the sides of hills. The rock shelters of ancient Europe, the Anasazi cliff dwellings of the American Southwest, and the Dogon houses of Bandiagara in the West African nation of Mali are all types of in-hill construction. The underground type of building is also ancient. Some of the oldest examples are found at Skara Brae in Scotland’s Orkney Islands; these buildings are 5,000 years old.

For ages, homes in warm wet climates have been built to accommodate the humidity. The traditional Malaysian house provides a good example. It is built on stilts, to allow airflow underneath. The walls do not absorb sunlight or heat. The interior is open so that air can flow throughout the building, which has a high roof peak to permit hot air to rise out of the building.

|

|

Photo courtesy of Chala Hadimi, © Aga Khan Visual Archive, MIT The tall structure at the top of the Iskendar Mausoleum, in Yazd, Iran, is a badgir, or windcatcher. The open tower captures breezes and helps provide natural ventilation in the hot climate. When there are no breezes, badgirs help release the heat inside buidings. |

In arid places such as ancient Persia (present-day Iran) and other warm countries, buildings had inner courtyards. The shaded courtyards opened into the buildings, allowing the cooler air to move in. If the courtyard included a fountain, the water helped through evaporative cooling. Iran is also noted for its badgirs, or windcatchers. These are open towers that can catch the winds and provide natural ventilation for buildings. If there are no breezes, they allow the hot air trapped in a building to escape. The thermal chimney also performs a similar function. The chimney is dark to absorb heat, and as the air inside it heats up it rises, creating an updraft. This pulls air from the rest of the building—thus creating air movement and pulling in cooler air.

|

ow Does Nature Do It? |

This content has been re-published with permission from SEED. Copyright © 2025 Schlumberger Excellence in Education Development (SEED), Inc.

.jpg?n=34)