Passive Heating Techniques

Photo courtesy of DOE/NREL, Robb Williamson

When a new visitor center was built for Zion National Park, Springdale, Utah, the U.S. National Park Service opted for a design that used many passive heating and cooling features. These include a trombe wall and clerestory windows. Sunlight passes through the whitish-colored glass and is absorbed by a thick masonry wall directly behind it. The masonry releases the heat to the interior of the building. The building opened in May 2000.

Passive heating uses the Sun for maximum effect. A successful passive house starts with building orientation. The longest wall of the building should face the equator, to get the most sunlight; in the Southern Hemisphere that wall faces north, while the orientation is reversed in the Northern Hemisphere. The side of the building facing the equator needs windows that are about 15% to 20% of floor area, to allow light to reach the interior walls.

The walls of the building need to have thermal mass. This means the walls are able to absorb the Sun’s heat during the day and release later, at night when the temperature cools. Materials that will do this include stone, concrete, and masonry. This is called direct gain of heat, because the sunlight hitting the walls creates immediate heat.

|

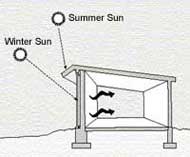

Image courtesy of U.S. Department of Energy This diagram shows how an overhang protects a trombe wall from the high summer Sun, but allows the lower angle Sun of the winter to reach the wall and thus absorb heat that can be released into the room.

|

|

A special type of exterior wall called a trombe wall also helps store heat from the Sun. A trombe wall is a thick, dark masonry wall with a single or double layer of glass over it, but not directly on top. The glass traps the Sun’s heat, and the masonry distributes it throughout the room. This process is called indirect gain of heat. The trombe wall design was patented in 1881 by Edward Morse but was popularized by French engineer Felix Trombe in the early 1960s.

The exterior walls are not the only ones that require thermal mass. Floors and interior walls of materials such as adobe, stone, or concrete can absorb heat that enters through windows. Bare floors of medium to dark colors absorb heat the best.

A sunroom or greenhouse room inside the house can trap a lot of Sun energy. Circulation loops distribute the heat throughout the house. The greenhouse can also be used to grow plants for food. The heat from a sunroom is called an isolated gain of heat, because its use is limited to one or a few rooms.

|

Seen from the interior, a trombe wall (with the sofa and lamps) looks like almost any other masonry wall. But at night, the wall releases the heat absorbed during the day.

|

This house in Tennessee uses stone for columns, walls, and floor, to provide thermal mass and absorb heat from the sunlight that comes in the south-facing windows.

|

A sunroom with masonry walls and floors absorbs heat from the Sun, which is later released as the house cools at night. |

Clerestory windows are a row of windows high along the roof line. They have a number of purposes. They can be used to add daylighting, reducing the amount of electricity needed to light up the room. On the sunny side of a building, they can add heat as well.

|

|

Photo courtesy of DOE/NREL, Robb Williamson The Zion National Park Visitor Center, Springdale, Utah, has a cooltower, which collects breezes to bring into the structure or allows heat to escape. This is the same concept as in the badgirs in Middle Eastern architecture. |

Other aspects of the house design can help passive heating. More commonly used rooms should be located on the warmer equator side of the building, with lesser-used spaces located on the cooler side. An open floor plan allows heat to circulate throughout the rooms.

A passive house should be well insulated. This keeps the warm air in during the winter and the cool air in during the summer. There are other ways to keep buildings cool in warm weather. Some of these depend on local climate. However, what works in a dry climate does not work as well in a wet climate.

This content has been re-published with permission from SEED. Copyright © 2025 Schlumberger Excellence in Education Development (SEED), Inc.