The 20th Century And On: Understanding the Immune System

Vaccines are based on the principle that once exposed to certain infections the human body develops an immunity that enables it to resist infection when it is exposed again. Immunization, or vaccination, creates the same response without exposing to the person to the actual disease. As we have seen, it was practiced in ancient China and introduced in the West by Edward Jenner. The basic science behind it, however, was not understood until the 20th century.

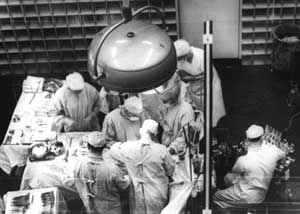

Image courtesy of National Archives of Plastic Surgery in the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine. The first kidney transplant was performed in Boston in 1954. |

In the 1880s the Russian biologist Elie Metchnikoff (1845-1916) developed the cellular theory of immunity. According to this, white blood cells serve as what he called "phagocytes" (literally, cell-eaters), detecting and consuming foreign organisms and debris within the body. Less than two decades later, Paul Ehrlich argued that the chief agents of immunity were antibodies, proteins produced by cells and released into the bloodstream. It turned out that both theories were correct, but the enormous complexities of the immune system continue to be unraveled to this day.

Progress in immunology has led to the identification of a whole class of disorders called autoimmune diseases. In these the human body fails to recognize its own constituent parts and mounts an immune response against its own cells. Well-known autoimmune diseases include type 1 diabetes, lupus, muscular dystrophy, and rheumatoid arthritis.

Immunological research has also led to the development of immunotherapy, the use of drugs to alter the immune system. As one might expect, immunosuppressive drugs are used to treat the autoimmune diseases. However, they are also critical to the success of organ transplantation. The successful first kidney transplants occurred in the 1950s, and the first heart transplant in 1967. None of the patients survived for all that long, however, because their bodies’ immune systems rejected the new organs. Cyclosporins, the first effective immunosuppressive drug for this purpose, were introduced in the 1980s. Immunosuppressive drugs gradually transformed organ transplantation into an almost routine procedure. Now—in one of the miracles of modern surgery—virtually any organ of the human body can be transplanted from one person to another. The limitation lies chiefly in the availability of organs.

Immune therapy is also a promising weapon in the fight against some cancers.

|

Image courtesy of World Health Organization. Caring for people with AIDS has stretched Africa’s health care systems to their limits. |

AIDS, first identified in the 1980s, brought the science of immunology to new prominence. Caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), AIDS destroys the immune system and thus the body’s ability to resist infection. The disease was initially considered a death sentence, but antiretroviral drug treatments can now prolong the lives of those infected for many years. However, AIDS still has no cure.

The immune system is one mystery that is slowly being untangled by scientists and physicians. Genetics is another. In the 20th century, understanding of this very complex field has become the centerpiece of a significant amount of research.

This content has been re-published with permission from SEED. Copyright © 2025 Schlumberger Excellence in Education Development (SEED), Inc.