The Rise of Scientific Medicine: The Scientific Revolution

Extraordinary advances

During the 17th and 18th centuries, scientific and medical knowledge advanced at an extraordinary pace. Many of Galen’s misconceptions were finally overturned. The Englishman William Harvey (1578-1657) accurately described the circulation of blood in the body, confirming the findings of earlier scholars (such as Ibn Nafis and more recent Europeans). He added the critical experimental finding that blood is "pumped" around the body by the heart.

|

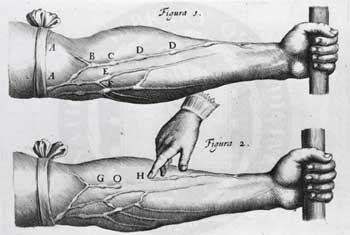

Image courtesy of National Library of Medicine. Physician William Harvey described the circulation of blood within the body. The engraving shows where to place a tourniquet to stop bleeding in an arm. It comes from one of Harvey’s texts on circulation. |

Harvey’s work was pursued by others, including English physician Richard Lower (1631-91). He and the British philosopher Robert Hooke (1635-1703) conducted experiments that showed that blood picks up something during its passage through the lungs, changing its color to bright red. [In the 18th century French chemist Antoine Lavoisier (1743-1794) discovered oxygen. Only then was the physiology of respiration fully understood.] Lower also performed the first blood transfusions, from animal to animal and from human to human. Hooke and, above all, the Dutch biologist Anton van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) used a new gadget called the microscope to discover all manner of tiny ("microscopic") things: red blood cells, bacteria, and protozoa. In Italy, physiologist Marcello Malpighi (1628-1694) used the microscope to study the structure of the liver, skin, lungs, spleen, glands, and brain. Several microscopic parts of the body, including a skin layer and parts of the spleen and kidney, were named after him. Malpighi also spurred the science of embryology by his studies of chicken eggs. As always, there were errors and misconceptions. Another Dutchman, physicist Nicolaas Hartsoeker (1656-1725), thought his microscope revealed little men ("homunculi") within spermatozoa in semen; he thus explained conception.

Digging Deeper |

|

Find out more about |

The 18th century, known as the Age of Enlightenment, was an era of progress in many respects. Interestingly, though, the desire to find a single all-encompassing explanation for "life, the universe, and everything" had not disappeared. Now, some thinkers attributed the workings of the body to newly discovered laws of physics, while others looked to the laws of chemistry. One approach called vitalism proposed the existence of an anima, or sensitive soul, which regulated the body. Another approach viewed disease as a disruption of the body’s tonus, which in turn was controlled by "nervous ether" from the brain.

Simple explanations led to sometimes dangerously simple treatments. An 18th-century doctor from Scotland named John Brown (1735–88) decided that all disease was due to excessive or insufficient stimulation. He therefore prescribed huge doses of sedatives and stimulants, causing great harm and great controversy. Homeopathy, another all-encompassing medical philosophy, developed about the same time. It calls for treating a patient’s symptoms by drugs that produced the same symptoms. The drugs are given in miniscule quantities, and are therefore harmless. Although Brown’s approach has disappeared, homeopathy still has its passionate followers.

|

The invention of the stethoscope by René- Théophile- Marie- Hyacinthe Laënnec enabled physicians to listen to the sounds of internal organs. |

Nevertheless, medical science was developing rapidly. The Italian anatomist Giovanni Morgagni (1682-1771) was credited with founding the discipline of pathological anatomy. He demonstrated that specific diseases were located in specific organs. Marie-François Bichat (1771-1802), a French physiologist, realized that diseases attacked tissues rather than whole organs.

Some of the advances were in diagnostics. The Englishman Thomas Willis (1621-75) analyzed urine and noted and presence of sugar in the urine of diabetics. The Dutch professor Hermann Boerhaave (1668-1738) began to use the thermometer, to note changes in the body’s temperature, in clinical practice. (He is also credited with establishing the modern style of clinical teaching at the University of Leiden.) Austrian physician Leopold Auenbrugger (1722-1809) noted the importance of tapping on the chest to detect fluid in the lungs. The Frenchman René-Théophile-Marie-Hyacinthe Laënnec (1781-1826) made the process easier by inventing the stethoscope. This instrument, which made it possible to listen to the internal organs, was the most important diagnostic invention until Wilhelm Roentgen discovery of X-rays in 1895. Laënnec’s stethoscope was a wooden tube, similar to an ear trumpet, the earliest form of hearing aid. The familiar modern instrument with rubber tubing and two earpieces was invented later, by American George Camman, in 1852.

There were major developments in therapeutics. Thomas Sydenham (1624-89), an English physician, advocated the use of quinine-containing cinchona bark, also called Peruvian bark, for the treatment of malaria. He also emphasized observation over theory, stressing the importance of environmental factors on health. An English naval surgeon called James Lind (1716-94) proved that citrus fruits cure scurvy, an unpleasant vitamin C deficiency disease that afflicted ship crews on long voyages. William Withering (1741-99), a botanist as well as a physician from England, noted the effectiveness of digitalis (from the foxglove plant) in treating heart disorders. And a British country doctor, Edward Jenner (1749-1823), developed the smallpox vaccine. Vaccination was so effective that this epidemic disease has now been eradicated worldwide.

And yet few of these and other advances in scientific knowledge and technology affected day-to-day clinical practice at that time. The main treatments continued to be cupping, bleeding, and purging. As recommended by Paracelsus and others, syphilis and other venereal diseases were treated with massive, often fatal, doses of mercury. Theriac, Galen’s famous all-purpose recipe, remained popular. There remained a huge gulf between scholarly medicine and everyday practitioners. Many of these practitioners and their patients were simply reluctant to adopt the new ideas. William Harvey famously complained that he lost patients after publishing his findings about the circulation of blood.

All the new knowledge still had not changed medical practice. Those changes came in the next century.

|

Image courtesy of National Library of Medicine. This cartoon shows Edward Jenner injecting patients with cowpox. Jenner found that cowpox infection protected people against the much more dangerous smallpox. This was one of the first vaccines to prevent a disease. |

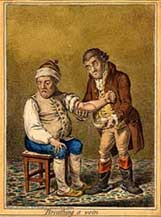

Image courtesy of Historical Collections & Services, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia. Bleeding, also known as breathing a vein, continued to be standard treatment well into the 19th century. |

|

|

Image courtesy of National Library of Medicine.

Cholera treatments from the 18th century include bundling the patient. |

Image courtesy of National Library of Medicine. In the 18th century, the village surgeon treated all family members. |

This content has been re-published with permission from SEED. Copyright © 2025 Schlumberger Excellence in Education Development (SEED), Inc.