Chinese Traditions Find a Place in Modern Medicine

|

Huang Ti, known as the "Yellow Emperor", is believed to have written the earliest known Chinese medical texts. (Credit: National Library of Medicine). Yin/Yang |

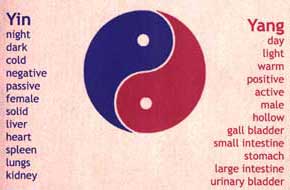

Images courtesy of National Library of Medicine. Ancient Chinese physicians believed that interactions between the yin elements and the yang elements controlled health. A modern yin and yang chart indicates the category of different organs of the body. |

The theoretical basis of Chinese medicine is laid out in the text called the Huangdi Neijing, or Book of Medicine of the Yellow Emperor. This book was probably compiled in the 1st century BCE and given its definitive form in the 11th century CE. It incorporates concepts that go back to the Shang dynasty (2d millennium BCE). Key ones include yin-yang (the balance of opposites) and Dao (the way of the universe), both of which became part of the Daoist religious tradition. It also provides detail on the concept of elements and humors.

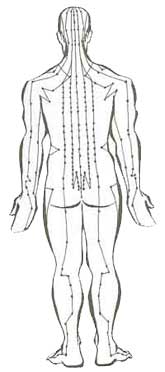

Image courtesy ofwww.smartaichi.com/. In acupuncture, the body is divided by meridian lines. Stimulating certain points along these meridians by inserting and twirling needles releases blocked energy, thereby initiating a cure. |

| The Chinese identified five elements of nature—wood, fire, earth, metal, and water. These were thought to correspond to the following: | |

| • | The five major (yin or zang) organs—liver, heart, spleen, lung, and kidney |

| • | The five auxiliary (yang or zu) organs—gall bladder, small intestine, stomach, colon, and bladder |

| • | The five sensory organs of the body—eyes, tongue, mouth, nose, and ears |

| • | The five fluids—tears, sweat, saliva, mucus, and urine |

|

Photo © Margery H. Freeman 1997. Cupping is a traditional Chinese treatment that uses glass, clay, or bamboo cups to create a vacuum on the skin, to facilitate healing. The man receiving treatment in this photo is in Vietnam. |

There are many other correspondences as well. Bodily functions depend on the interplay between yin and yang and the passage through the body of qi (energy), which flows through body in channels, or meridians. Disease is the result of disruption of these processes.

The Neijing explains the complex art of pulse-taking, which was the principal diagnostic tool of the Chinese physician. It also includes a classic description of acupuncture, one of traditional Chinese medicine’s best known therapies. Acupuncture involves inserting fine needles into various points of the body along the meridian lines. The insertion and twirling of the needles was believed to restore and rebalance the flow of qi. Another ancient technique used to restore qi was moxibustion, the practice of burning bundles of the herb mugwort on the skin.

Although the emphasis was on the internal causation of a disease, traditional Chinese medicine recognized that outside factors played a role. A 2d-century CE physician called Zhang Zhongjing wrote the Treatise of Cold-Damage Disorders, which described the diagnosis and treatment of diseases caused by external cold factors; in effect, this referred to infectious diseases.

|

Image courtesy of National Library of Medicine. The Bencao Gangmu is a comprehensive text of traditional Chinese medicine. It was written by Li Shih-chen and was first published in 1593 during the Ming dynasty. |

The treatment for most disorders was drug therapy. A huge compendium called the Bencao Gang Mu, completed in the 16th century, lists all the plants, animals, and minerals that were believed to be medically useful. It includes many treatments that continue to be used today, including opium, ephedrine, rhubarb, iron, and many other drugs. There is some evidence that the Chinese also practiced an early form of immunization for smallpox. There are 10th-century paintings that appear to depict physicians having patients inhale dust from smallpox scabs.

Surgery, on the other hand, was virtually unknown. There is a record of only one surgeon in early Chinese history, a man called Hua To, who lived in the 3d century CE. According to one account, he used a form of anesthesia made of wine and herbs. He was said to have been on the verge of removing a brain tumor when his suspicious princely patient ordered his execution instead.

|

Image courtesy of Long Bow Group Archives. Barefoot doctors During the years of Communist rule in China, so-called "barefoot doctors" were trained in traditional Chinese medicine. This group of such doctors is seen at the 1969 National Day celebration in Tiananmen Square. |

For much of Chinese history, practical care of the sick was provided by a variety of healers. Some had training in the medical theories and arts described, but many did not. Buddhist monasteries established hospices for the care of the dying and clinics for the treatment of the sick. The government took over these clinics in the 9th century and sponsored the compilations such as the Bencao. Later private clinics became the principal source of care. In the 19th century Christian missionaries established hospitals and training in Western medicine. China’s Nationalist government attempted to establish a state medical system based on modern Western practices. The Communist government took that over but also developed a system of "barefoot doctors" to supplement it. The barefoot doctors were essentially trained only in traditional Chinese medicine.

|

Image courtesy of Dreamstime. Acupuncture continues to be used around the world.

|

In Europe and the western hemisphere, traditional Chinese medicine has been adopted as complementary or alternative medicine. Acupuncture in particular has developed a wider following. Although the scientific mechanisms by which it works remain unclear, this ancient form of treatment is clearly effective in relieving some forms of pain.

Ancient India also developed traditional medical practices that have survived to this day.

This content has been re-published with permission from SEED. Copyright © 2025 Schlumberger Excellence in Education Development (SEED), Inc.

.jpg)