The 20th Century And On: Drugs to Treat Sicknesses

The pace of medical advances quickened on all fronts in the 20th century. Breakthroughs came in biology, chemistry, physiology, pharmacology, and technology, often in converging or overlapping ways. New understanding of diseases brought new treatments and cures for many of these conditions. However, even as most of the killer epidemic diseases were conquered—and in the case of smallpox erased—new diseases emerged, such as AIDS.

Photo © The Nobel Foundation. German bacteriologist Paul Ehrlich developed the concept of using a drug to attack a single organism within the body. This led to the development of drugs to treat illnesses such as syphilis. |

|

Photocoutesy of Fotosearch. Penicillin, magnified here, was the first antibiotic used to kill bacterial infections. |

During the 20th century life spans lengthened in most parts of the world. The flip side of this was the increased prominence the diseases of aging, above all, heart disease and cancer, and a focus on treating and preventing these diseases. In a worrying development, some diseases that appeared to have been conquered by drug treatments, such as tuberculosis, developed resistance to those medications toward the end of the 20th century.

Drugs to treat sicknesses

Toward the end of the 19th century the study of herbal, chemical, and mineral remedies (what was called material medica) was transformed into the laboratory science of pharmacology. Plant drugs such as opium underwent systematic chemical analysis. Researchers then learned how to synthesize these drugs. By the turn of the 20th century the pharmaceutical industry was marketing laboratory products. A company called Bayer in Germany trademarked a synthesized version of acetylsalicylic acid that it called aspirin.

A pioneer in pharmacology was the German scientist Paul Ehrlich (1854-1915), who—after much trial and effort—synthesized the arsenic-based compound Salvarsan, the first effective treatment for syphilis, in 1909. Ehrlich, who coined the term "chemotherapy," thus created the first antibiotic drug. A generation later, another German, Gerhard Domagk (1895-1964), who worked for Bayer, produced the first useful sulfa drug (another antibiotic). This drug was used to treat streptoccal, or strep, diseases, including meningitis.

Scientists also researched biological antibiotic agents. The ancient Chinese, Egyptians, and Greeks had all found that moldy substances were effective in keeping cuts clean. Pasteur observed an antibacterial action when he noted that the addition of common bacteria stopped the growth of anthrax bacilli in sterile urine.

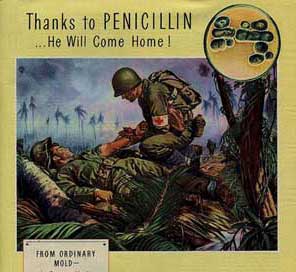

In the 1920s the Scotsman Alexander Fleming (1881-1955) found a mold growing on some bacterial samples in his laboratory. In fact, the mold killed the samples. He identified the mold as penicillin. During World War II a team of researchers led by Australian Howard Florey (1898-1968) furthered that research and tested the new drug on injured soldiers. It proved effective against anthrax, tetanus, and syphilis and was the first drug that worked against pneumonia. About the same time Selman Waksman (1888-1973), an American biochemist, isolated another fungoid, streptomycin, which proved effective against tuberculosis. Waksman coined the term "antibiotic" to describe especially the biological drugs.

|

Image courtesy of Research and Development Division, Schenley Laboratories, Inc., Lawrenceburg, Indiana. During World War II, penicillin saved the lives of many soldiers |

Many new drugs followed in the 1950s, including cortisone, a steroid hormone that reduced inflammation and suppressed the immune system response. The first effective drugs for the treatment of mental illness also appeared in this era.

Although antibiotics did not work against viral diseases, antiviral vaccines did. Two of the most important were the vaccines against smallpox and polio. Polio, chiefly a disease of childhood, causes paralysis. Two American scientists, Jonas Salk (1914-95) and Albert Sabin (1906-93), developed different versions of a polio vaccine, which were introduced in the mid-1950s. Salk’s vaccine was based on the dead virus, while Sabin’s was based on the live one. Both were used, with great success. Polio was mostly eradicated by the end of the 20th century.

.jpg) Image courtesy of The March of Dimes, with the kind permission of the Salk family. Jonas Salk administers a polio vaccine to a young student. |

Other antiviral vaccines include those for measles, chickenpox, and influenza. Vaccines against human papillomavirus (a cause of cervical cancer) and shingles (a relative of chickenpox caused by herpes) became available in 2006. Efforts to develop a vaccine against malaria and AIDS have so far proved unsuccessful.

The first antiviral drug, acyclovir, appeared in the 1970s for use against some forms of herpes. Antiretroviral drugs were developed in the 1980s to combat AIDS. (Retroviruses are a class of virus.) Viruses mutate so quickly, however, that developing antiviral (and antiretroviral) agents has proved very difficult.

Researchers have used many different approaches to developing drugs for patients. One major revolution for treating illnesses was a new understanding of the immune system.

This content has been re-published with permission from SEED. Copyright © 2025 Schlumberger Excellence in Education Development (SEED), Inc.