The Breakthrough

Lots of soot with many fullerenes

Solution extracted Jonathan Hare

from the carbon soot

Kroto returned to England and tried to somehow make enough C60 to enable a structural analysis. This was in the late 1980's, when both Jonathan Hare and myself embarked on postgraduate research in Chemistry. Jonathan worked with Kroto on the isolation of C60 and I simulated the behaviour of carbon clusters in the theoretical chemistry group of John Murrell.

Experiments over weeks and weeks with a carbon-arc in a helium filled bell-jar yielded a soot that contained C60 in much larger quantities than expected. Jonathan then extracted a beautiful red solution from the carbon soot, containing mainly C60.

But before these findings could be written up, Harry Kroto received a fax asking him to referee a paper for Nature by a German/American team, Wolfgang Kraetschmer & Don Huffman, who had managed to crystalise C60 and determine its structure by X-ray. To Kroto's dismay, it contained the very results he was hoping to find himself!

The carbon arc-method was such a simple way to produce C60! With the publication of the Kraetschmer/Huffman article, research groups all over the world built carbon-arc fullerene generators and started to investigate this fascinating molecule. Even schools have succeeded in making C60. Theoreticians like Patrick Fowler (Exeter, UK) wondered how many different fullerenes there are and how they could form so easily. I contributed to the latter debate with an article in Science, "Auto-catalysis during Carbon Growth".

|

|

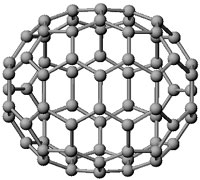

Above: C70 molecule

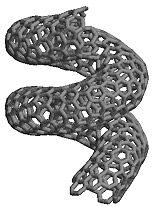

Below: Nanotube |

|

|

But there's more! It soon turned out that there were other cage structures to be found in the soot, like C70, which looks a bit like a rugby-ball (American football).

Even more interesting, when the carbon arc power supply was changed to direct current instead of alternating current, strange tubular structures could be found in one of the electrode's deposits. These tubes are entirely made out of carbon and were named nanotubes, referring to their diameters, which are only a few nanometers wide. They were first observed and reported in 1991 by a Japanese scientist, Sumio Iijima.

Since then, several other methods have been devised to produce carbon nanotubes including:

- electrolysis using graphite electrodes in molten salts;

- catalysed pyrolysis of hydrocarbons;

- laser vaporisation of graphite.

A straight single-walled nanotube can be made by rolling a flat graphitic sheet into a cylinder. This can be done in various ways, resulting in different kind of nanotubes (called "armchair", "zigzag" and "chiral"). Depending on the exact arrangement they exhibit different electronic properties, some are predicted to be metallic while others are semiconductors.

One can also introduce "defects" into the straight tube, which is made up from carbon atoms binding exclusively in hexagon patterns by reducing or adding one carbon bond. The resulting pentagons and heptagons can introduce kinks, curvature and the like. So it is possible to create nano-spirals, nano-doughnuts, capped-ends on tubes ... which have all been observed.

These nanotubes are incredibly strong - several hundred times stronger than steel, partly because of the hexagonal geometry, which can distribute forces and deformations widely and partly because of the strength of the carbon-carbon bond! As mentioned above, they have unusual electronic properties. Already simple electronic devices, such as diodes, switches and transistors have been realized using nanotubes, which are much smaller than their silicon equivalents used in today's computer chips.

Research is under way to produce carbon nanotubes reliably and under defined conditions. When such methods have been found, nanotubes will appear in electronic devices and also in new, super strong materials.

This content has been re-published with permission from SEED. Copyright © 2025 Schlumberger Excellence in Education Development (SEED), Inc.