Beginning The Search

Carbon is one of the most versatile of the chemical elements and forms the backbone of almost all molecules important to life, such as DNA, proteins and oils. The unique character of carbon stems from its ability to form stable bonds with itself - most other elements prefer different partners in chemical bonds.

|

Diamond |

Graphite |

|

|

|

|

Carbon Chain

|

It may therefore be surprising to realise that this element, which forms more chemical compounds with a few other elements (i.e. hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen) than all the 100 or so elements combined, exists in only two pure forms: diamond and graphite. In diamond every atom is surrounded by four other carbons, forming a three-dimensional network, whereas in graphite every carbon bonds with three neighbouring atoms in a plane, leading to a chicken-wire like sheet. These graphitic sheets are loosely coupled with one another and slide easily, giving it a soft texture.

These are the only two forms of pure carbon. Or so we thought until recently!

In diamond every carbon atom has four connections and in graphite the number drops to three. If only two connections are allowed, a chain of carbon atoms would result.

Evidence of the first fragile all-carbon chains were seen in the 1940's in experiments by Otto Hahn, to whom this was just an unwanted side effect observed while trying to create larger, heavier atoms by attaching neutrons to them. Hahn was interested in detecting small differences in the mass of certain heavy metal atoms, evaporated in a carbon arc. While observing his results, he noticed that the arc also produced carbon chains, which coincidentally had the same mass as the metal. Hahn switched to different electrodes, reported the occurrence of the carbon chains in a footnote and carried on with his main research. His results on the carbon chains were not followed up immediately, so the discovery of C60 was destined to go missing for several decades.

Chains in the Sky

Two branches of chemistry emerging in the 1970's, Astrophysical Chemistry and Cluster Science, opened the way for some exiting discoveries with the help of Radioastronomy. Radiosignals generated by vast clouds of millions of tons of gas in interstellar space could be used to detect molecules. Researchers also found strange molecules that had not been synthesized in the laboratory! Meanwhile, back on earth new methods of generating and detecting aggregates of atoms in the laboratory that stuck together in novel ways led to a new class of molecules, called clusters. Typically clusters are in a transition zone between molecules and solids and their properties reflect this strongly. Chains and other aggregates of carbon atoms can be considered as clusters.

At Sussex, England, Harry Kroto and Dave Walton were synthesising long carbon chains, terminated with hydrogen on one end and with nitrogen on the other. They found that the spectroscopic patterns, of these substances were identical to certain absorption/emission peaks seen in vast gas clouds in our galaxy, the Milky Way. They also detected signals from these clouds that were hinting at even longer carbon chains than those they could synthesise on earth. The concentration of these long molecules was much higher than anyone expected. The scientists wondered where they came from.

|

Carbon Star (Red giant) |

A possible solution lay in the stars, which generate their energy by fusing light elements (like hydrogen) into heavier ones. Stars can be small, called white dwarfs or large, called red giants. Our sun is somewhere in between those two extremes. The source of these long carbon molecules was finally found in cool red giant carbon stars, which have run out of primary hydrogen fuel and are now "burning" helium atoms. This carbon is then blown into the interstellar space.

The old paradigm that pure carbon was found in nature as graphite or diamond was overturned.

Clusters and Balls

Eventually, in 1985, Kroto persuaded an American colleague, Rick Smalley, to collaborate on a project to simulate conditions of such red giant stars in the laboratory.

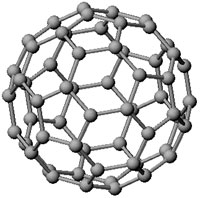

In Smalley's machine, a powerful laser evaporated a bit of graphite into a hot cloud of particles that were cooled with a stream of helium gas, allowing atoms to condense into clusters. The mixture was analysed with a very sensitive apparatus called a mass-spectrometer, which indicated a large number of molecules with a mass of 720. The only elements present were helium and carbon. Since helium is a totally inert gas, the conclusions was that the large molecules must be made of 60 carbon atoms, each of which has a mass of 12. The peak at 720 on the graph produced by the mass spectrometer was strong, much stronger than neighboring peaks, which means that C60 can form and survive in the high-energy environment of a mass-spectrometer, where many other molecules break up (fragment) in a characteristic way, allowing identification. This could only mean that a collection of 60 carbon atoms was somehow extraordinarily stable.

|

A C60 molecule known as a fullerene

|

The researchers faced a dilemma: the mass-spectrum showed clear evidence of C60, but the amounts detected were by far too small to allow a structural analysis. Several days of brainstorming produced a beautiful, but also risky hypothesis: the 60 carbon atoms arranged themselves to look like a football or an American soccer ball. Due to its structural symmetry, which featured prominently at the time in some constructions of the architect Buckminster Fuller, the scientists named the molecule buckminsterfullerene. The exact chemical name is very cumbersome!* Buckminsterfullerene is often shortened to fullerene or buckyball. The team published their claim in the eminent journal Nature. The symmetric structure of the molecule was was a hypothesis and it was important to gather direct proof of the geometry in order to claim this to be unquestionably true.

In the preceding decades, some chemists had laboriously synthesised highly symmetric carbon cages (terminated by hydrogen atoms), the largest one being dodecahedrane C20H20, and there were so many reaction steps involved (each reducing the final yield further) that anything bigger was not attempted. That a molecule three times as large as dodecahedrane would form spontaneously just by heating up graphite was considered almost magic. It was just too easy!

But it was true, and large quantities of C60 were about to be synthesized!

This content has been re-published with permission from SEED. Copyright © 2025 Schlumberger Excellence in Education Development (SEED), Inc.