Digging Deeper: Common Myths about Lightning

- Can lightning happen without thunder or thunder without lightning? Are lightning and thunder the same thing? No and no. Where there’s lightning, there’s always thunder. The intense heat of lightning creates thunder by quickly expanding the air, which produces sound waves (vibrations) and a shock wave.

- Does lightning only strike in thunderstorms? No. Volcanic eruptions can produce an exploding, expanding, churning cloud of ash that disrupts the sky’s electrical balance, creating spectacular shows of lightning. Similar violent turbulence can spark lightning in the heavy smoke of wildfires, heavy snowstorms, and nuclear-bomb explosions.

- Can lightning strike the same place twice? Absolutely. The lightning rod atop the Empire State Building in New York City takes several hundred hits each year.

- Is lightning white? A bolt of lightning is a powerful arc of electrical current that flows through the air for a split second. The arc’s enormously high electrical energy rips apart the gas molecules in the air and excites their electrons to produce photons across a wide spectrum of frequencies that depend on what type of molecules are in the air. Typically, the spectrum in air is so wide that the arc starts off as white. However, the apparent color of lightning depends on what’s in the air to scatter that light between you and the bolt of lightning. There could be rain, hail, dust, or pollution that can make the light appear blue or yellowish, or there could be simply clear air—in which case the lightning bolt would appear whiter.

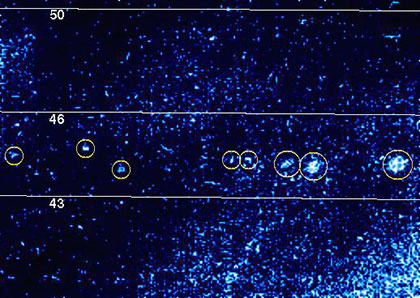

- Does lightning strike only on Earth? No. Space probes have detected lightning strikes and other evidence of electrical activity on several planets with atmospheres, including Jupiter, Venus, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. As NASA’s New Horizons probe revealed in 2007, Jupiter is unusual in that lightning strikes the north and south poles (latitude 90°). This close-up of the giant gas planet, taken by Galileo in 1997, captured a series of lightning flashes (circled) between latitudes 43° and 46°.

Photo courtesy of NASA/Jet Propulsion Lab.Astronomers believe that the bright spots, circled on this image, are lightning striking on Jupiter.

This content has been re-published with permission from SEED. Copyright © 2025 Schlumberger Excellence in Education Development (SEED), Inc.